I’m still working on my 1941 Stromberg-Carlson 520-PG and am running into a few new problems I’ve never come across before. Back in the era of tube radios, everything was serviceable on a component level and most people had enough aptitude and desire to learn that it wasn’t uncommon for people to attempt repairs themselves. You also had “radio technicians” who may or may not have been reputably trained and were frequently turned loose on people’s equipment for the lowest bid.

This was definitely the case with my radio, as I’m discovering evidence of someone else having been inside and attempted repairs that were of dubious quality and may never have worked properly in the first place.

It’s pretty easy to tell if someone has made repairs before. Component brands is the easiest method, at least for major-brand radio sets from that time period. Most of the capacitors in this Stromberg-Carlson set were branded with that name, but Mallory capacitors made a couple of appearances too. These were clearly replacements, S-C .01uF capacitor on top and a Mallory .01uF capacitor on the bottom. Making it worse, the solder job was so bad I was able to slide the entire joint up and down along its wire – I doubt there was ever an electrical connection between the wires, even though they were physically fixed together.

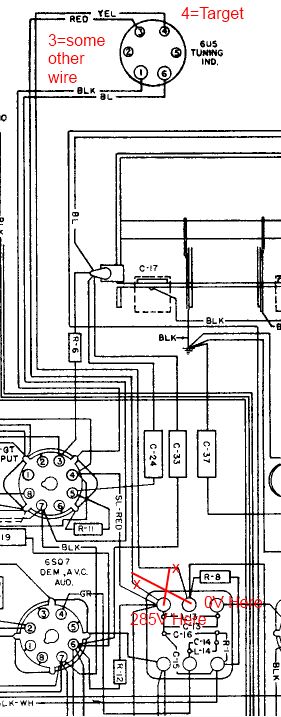

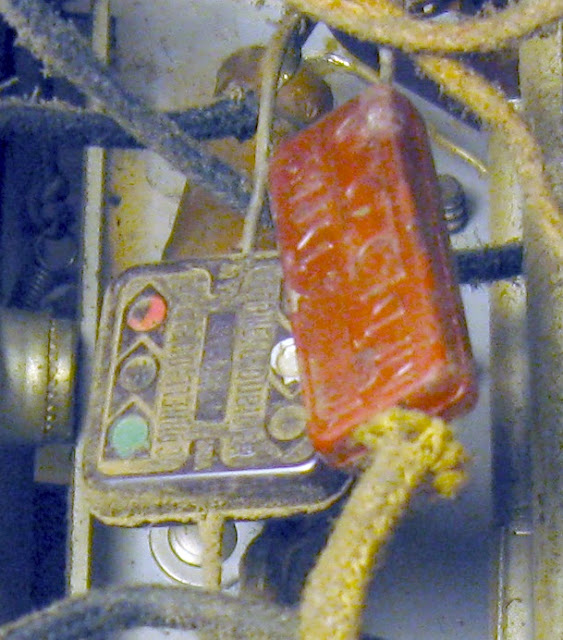

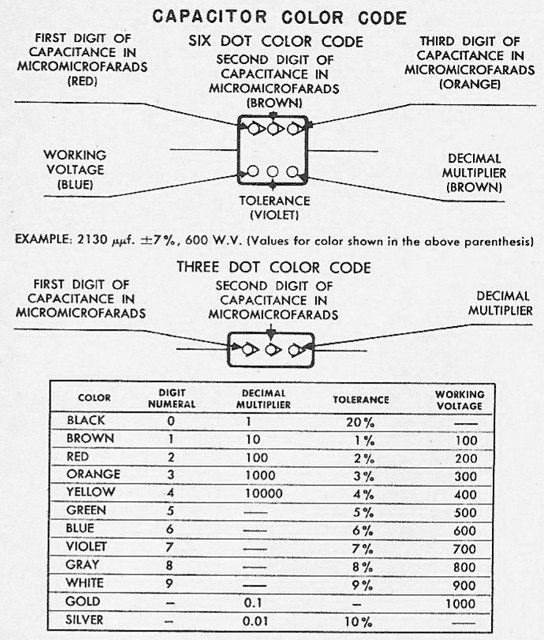

There’s also an extra part not listed on the schematic, bypassing the high voltage plate resistor for the audio amplifier tube to ground. I speculate this was done to eliminate some interference from getting into the audio, but it’s another modification that is of unknown quality. The capacitor, the block with colored dots, has started to fail after ~70 years and occasionally introduces some static into the audio as it’s playing. (The capacitor is across R-6 on the schematic snip slightly lower on the page.)

Finally, there are wiring changes made that don’t match the schematic. Is the schematic wrong, or is the wiring in the radio wrong? Schematics of the day were hand-drawn by draftsmen who frequently worked long hours revising and publishing schematics and service data, and mistakes are not unheard of.

I’ve been in other radios that have shown evidence of previous repairs, like this Packard Bell 35-Late which has 5 different brands of capacitors from 3 distinct eras of materials, but were all wired correctly. Pretty much every one of the cylinders except for the tiniest ones is a capacitor in this photo:

or this Zenith 7-S-363 which used both Zenith- and Mallory-branded capacitors from the factory, and also contained Aerovox and Solar later replacements but also worked perfectly after repair:

This Stromberg-Carlson is the first radio I’ve serviced where there were clear mistakes made along the way. It’s an entirely new set of challenges on top of the already-difficult antique radio repair process, but it does add a level of fun and discovery that a straight-up easy “recap” repair doesn’t offer.

Edit: After some peer review, it turns out it was a draftman’s error between the schematic diagram and the wiring diagram! Annoying. I should publish some errata, maybe I’ll do that soon.

Burned Up Aiphone

This is what happens when you connect the high level output of an audio amplifier, to an input designed to be hooked up to an MP3 player or other line level audio source. This Aiphone PA amplifier was incorrectly installed by a technician and it made this 1/2W resistor dissipate about 40W. It held up…briefly…but quickly turned into a charred mess. It was somehow managing to pass a terribly distorted signal but didn’t damage any other components. After replacing the resistor on this pictured unit, and another identical one damaged the same way, it was back in service.

It’s not always overly aggressive cost engineering that makes things fry. Sometimes it is actually operator error.

Share this: